Empathy With Animals And With Humans: Are They Linked?

Associations between Oxytocin Receptor Factor Polymorphisms, Empathy towards Animals and Implicit Associations towards Animals

1

Scotland's Rural Higher (SRUC), West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 three JG, United kingdom

2

Roslin Establish, University of Edinburgh, Penicuik EH25 9RG, UK

*

Writer to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received: 26 July 2018 / Revised: 9 August 2018 / Accepted: 12 August 2018 / Published: 14 Baronial 2018

Elementary Summary

Oxytocin is a hormone which acts as a neurotransmitter has been associated with a wide range of homo social behaviours. Unmarried nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) inside the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) accept been described to exist involved with human-man empathy, however footling is known almost OXTR SNPs and human-brute empathy and spontaneous reactions towards animals. This has been investigated in the nowadays written report with 161 British students and five extensively studied OXTR SNPs. Validated, standardized measures for empathy towards animals and spontaneous reactions towards animals have been employed. Results indicate that females show higher levels of empathy and have more positive reactions towards animals than males. Furthermore, empathy towards animals was associated with the absence of the minor A allele on OXTR SNP rs2254298. These results indicate that OXTRs play a role not but for human social behaviours but likewise for human-animal interactions.

Abstract

Oxytocin has been well researched in association with psychological variables and is widely accustomed as a key modulator of human social behaviour. Previous work indicates involvement of oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in human-human empathy, yet piffling is known about associations of OXTR SNPs with empathy and affective reactions of humans towards animals. V OXTR SNPs previously found to associate with human social behaviour were genotyped in 161 students. Empathy towards animals and implicit associations were evaluated. A Full general Linear Model was used to investigate the OXTR alleles and allelic combinations forth with socio-demographic variables and their influence on empathy towards animals. Empathy towards animals showed a significant clan with OXTR SNP rs2254298; homozygous One thousand individuals reported higher levels of empathy towards animals than heterozygous (GA). Our preliminary findings show, for the first time, that betwixt allelic variation in OXTR and animal directed empathy in humans peradventure associated, suggesting that OXTRs social behaviour part crosses species boundaries, warranting independent replication.

1. Introduction

Man interactions with animals are manifold and it has been shown that human attitudes towards animals, that is, in particular positive attitudes towards animals, are of vital importance to the welfare of animals under human care [1]. It has been shown that attitudes towards animals are influenced by a variety of factors such as socio-cultural and religious norms [2,iii], early on life experiences [2], personality traits [iv], species preference [5,half dozen], the degree of interactions with animals [seven] and people's perceptions of the degree of cognitive and behavioural similarity betwixt humans and animals [eight,nine] to proper noun a few. This list is non conclusive and attitude enquiry by and large shows that only a small amount of variance (between 4–18% [iv,x] can be accounted for by a combination of aforementioned attitude modifiers).

Empathy has been suggested to be a strong and reliable predictor predominately for inter-human relationships contributing to an increase of positive attitudes and behaviour [11]. Empathy has been defined equally reactions of one individual to the observed experiences of another individual [12] encompassing both affective and cerebral components [13]. Empathy towards other humans has been a main predictor for maintaining pro-social relationships [14] and it has also been shown to improve attitudes to members of stigmatised groups [15]. Besides, empathy has also been reported to correlate with attitudes towards the treatment of non-human species [four,v,16]. Indeed associations take been found between human-human and human-animal directed empathy suggesting that the two types of empathy measures are in some way linked, although they are unlikely to tap a single unitary construct [17]. The relationships between covariates also suggest different sources of variation between man-human and human-animal empathy scores [17].

Empathy has been shown to influence farmer's attitudes and behaviour towards dairy cattle [18] and was shown to be positively correlated with milk yield [19]. Veterinarians with higher levels of empathy also showed amend pain recognition in cattle [20]. A study investigating dog owners' empathy and attitudes towards animals and their relationship with hurting perception in dogs revealed empathy to be a strong predictor of these hurting perceptions [21]. Empathy has therefore been suggested to be an important gene positively influencing human-animal interaction [ane]. An experimental study investigating dissimilar scenarios of the need for medical attending in an fauna or human being abuse victim, constitute that people show at least as much empathy for animals as for humans [22]. These results betoken that empathy for animals might interpret into prosocial behaviour towards them.

Human empathy has been linked with pro-social behaviour, social organisation and behaviour [11] in full general which are cardinal aspects in the success of many fauna species. Social behaviour which can involve both positive and negative interactions is a complex process involving the combined furnishings of hormones, genetics and by experience (reviewed in [23]). The ability to maintain social relationships has been proposed equally a need routed in human development with the inability to maintain social relationships, or of feelings of social exclusion, being associated with reduced psychological wellbeing [24]. Oxytocin (OT) a neurohypophyseal hormone, produced in the paraventricular nucleus and excreted by the pituitary is widely accepted as a central modulator to social and emotional behaviour in mammals [25]. Oxytocin's chief receptor (OXTR) is localized to chromosome 3p25 (in humans) and contains 28 known single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (https://www.snpedia.com/index.php/OXTR) [26], with various observed effects. Of these 28, 10 of these SNPs have been extensively studied in relation to social behaviour and psychological wellness in humans (reviewed in [27]). Associations take been recorded at various sites, with 2 OXTR SNPs, rs53576 and rs2254298 beingness particularly prevalent. Allelic variation at rs53579 has been linked to individual differences in pro-social temperament [28], stress reactivity [29], emotional back up seeking [30] and loneliness [31]. Variation at rs2254298 has been linked with maternal depression [32], depression and anxiety in adolescence [33]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that OXTR is associated with affective behaviours [34] and empathy (inter human empathy) [29] specifically with the sub-scale empathic concern [35] and trait empathy [36].

Intranasal administration of oxytocin in humans has been shown to increase trust [37], improve the estimation of social cues [38] and increase middle-gaze [39] in good for you individuals. However given OTs poor ability to cantankerous the claret encephalon barrier there is contend over the methodology of these studies and the manner of action of OT in such experiments [twoscore]. The result of intranasal OT administration is besides context and individual dependent (as reviewed in [41]) and it has been proposed that the interaction between individual differences in endogenous OT plasma levels and allelic variations in the oxytocin receptor factor (OXTR) may form complex interactions which modulate the furnishings of exogenously administered oxytocin on an individual basis. For example, the previously mentioned review paper from Bartz et al. (2011) [41] states that, of those studies tested, >40% showed no main upshot of OT and >sixty% reported individual differences as moderators. In some cases intranasal oxytocin actually produced antisocial behaviour traits, such as distrust [42] and envy [43].

While OXTR has been well researched in connectedness with psychological variables inside and between humans, little is known about its association with empathy and affective reactions towards not-homo species, though the reverse has been studied. In dogs treated with intranasal oxytocin, OXTR polymorphisms and their interaction were associated with dogs' human directed social skills [44,45,46]. However, the effect of OXTR polymorphisms, in the absence of an endogenous primer (such every bit intranasal OT), on brute directed empathy in humans has thus far not been tested. Based on the same associations of the OXTR with human-human empathy, the present study attempted to explore possible associations of the event of allelic variation at 5 known SNP loci in OXTR (rs2268491, rs13316193, rs4686302, rs2254298, rs53576) and homo-animal empathy and implicit associations towards animals. Implicit associations are associations which take been exposed by means of indirect or implicit measures [47]. Traditionally attitudes accept been assessed using self-written report measures which in turn take been criticised due to influences past uncontrolled extraneous variables like environmental factors, order of items, wording of items, that is, social desirability, specially in regard to sensitive topics [47,48]. Implicit associations tests aim to detect the strength of people's automatic associations betwixt mental representations of objects [47], that is, have been used in an attempt to access attitudes indirectly [47]. Our specific aim was to investigate whether empathy towards animals and/or implicit associations to animals share some of the same biological basis as for homo-human empathy past testing their association with OXTR SNPs known to associate with pro-social behaviour in human, hence adding to our understanding of the development of our perceptions and behaviour towards non-human animals. Considering the complication behind empathy modulation—that is, its novelty in the field of fauna welfare—there is scarce evidence that supports the belief that empathy provides another means to improve animal welfare. Since empathy expressions are contextual and affected by empathizer characteristics (e.g., pet-buying, gender) as well as the relationship between empathizer and target [49], a sample of animal care students and professionals, that is, non-creature intendance students and professionals were investigated.

two. Methods

2.1. Ethics

Sample and study design were approved past the National Health Service (NHS) research ethics commission for good for you volunteers (Accord) and the SRUC Research Ethics in Student Projects committee (REC code fourteen/HV/0005, IRAS project ID 154914). All individuals gave informed consent at the get-go of the study and were complimentary to withdraw at any time.

2.2. Measures

2.2.ane. Empathy Measures

Animal Empathy Scale (AES) was measured using the 22-item scale proposed by Paul (2000) [17]. Items were measured on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from I "completely disagree" to "fully agree." Reversed phrased items were re-coded for the analysis and a mean scale score was computed.

ii.2.two. Implicit Associations

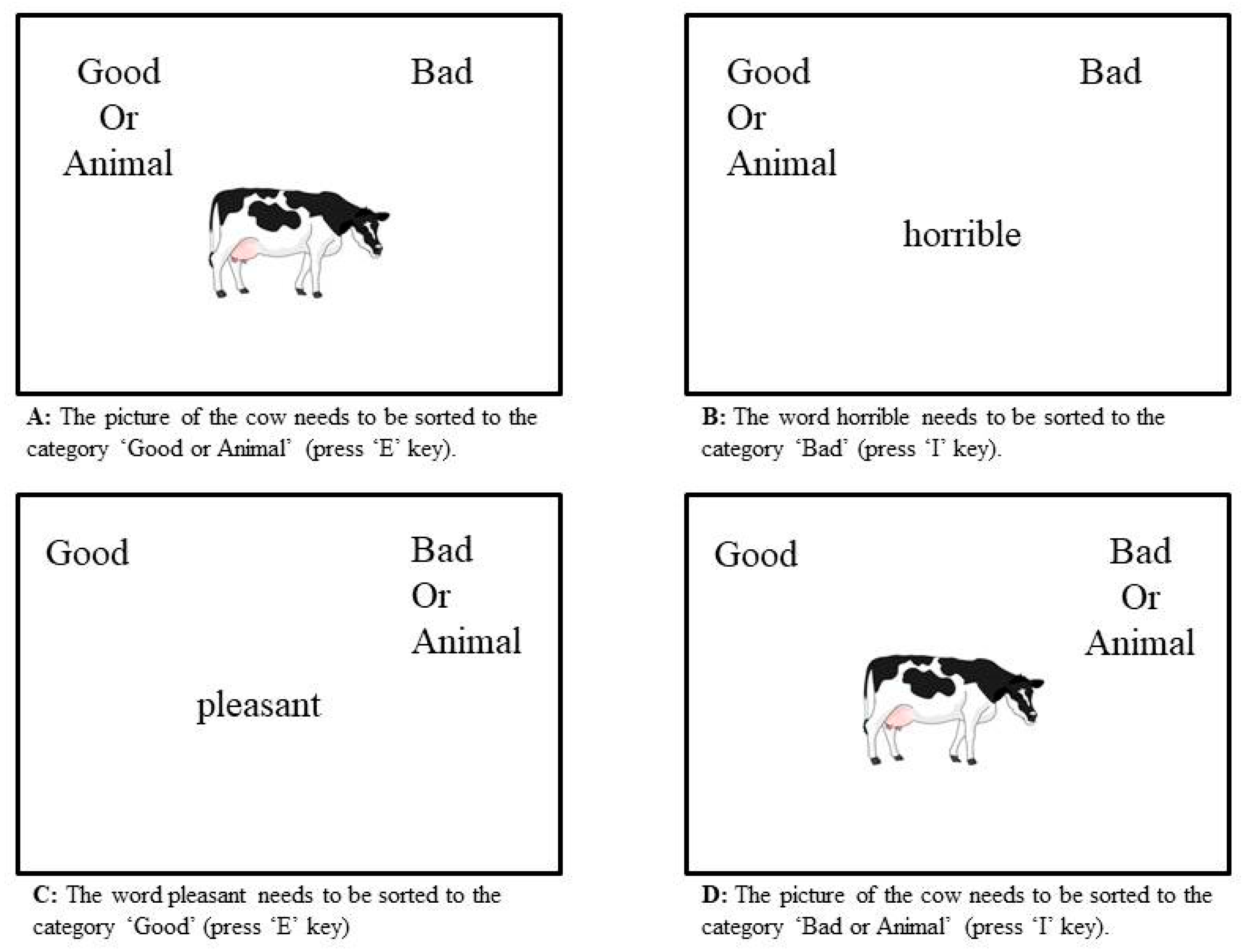

Implicit associations to animals were assessed using a unmarried category picture implicit association test (IAT), which has been adapted from the Karpinski and Steinman [50] IAT measure. The implicit association exam is a timed computer-based matching task [51] using Inquisit 4 (2014), Millisecond software. Participants were presented with positive attributes as positive words (celebrating, cheerful, fantabulous, excitement, fabulous, friendly, glad, glee, happy, laughing, likable, loving, marvellous, pleasure, smile, splendid, superb, paradise, triumph, wonderful), negative attributes as negative words (angry, brutal, destroy, dirty, disaster, disgusting, dislike, evil, gross, horrible, humiliate, nasty, baneful, painful, revolting, sickening, terrible, tragic, ugly, unpleasant, yucky) and animal pictures. In total 21 words for each aspect category were used forth with 12 drawn images of animals (from Sparklebox.co.uk) [52] randomly presented in the eye of the estimator screen, below the target categories. Animals used for the IAT included pet animals such as dog, rabbit, budgerigar; British farm animals such as cow, pig and sheep; and British wild animals such as deer and fox. Participants were instructed to utilise the 'I' and 'E' key on the keyboard to sort the animals into the target categories depending on the description of the task (task 1: sorting pictures of animals and positive words into the target category 'Good or Animals' (Figure 1A); task 2: sorting pictures of animals and negative words into the target category 'Bad or Animals' (Effigy 1D). An IAT score was generated by the programme based on the participant's latency to respond and error rates. The program automatically records and summarises false responses (when respondents categorized the attributes (words and pictures) to the wrong target category) and as well irksome responses (>500 ms) [50]. The IAT score corresponds to participant'due south implicit associations with the target category in this case animals [50].

2.3. Saliva Sampling and Dna Extraction

Participant saliva was collected using the 'Saliva Dna Collection, Preservation and Isolation Kit' from Norgen Biotek (Ontario, ON, Canada) as per the manufacturer'south instructions. Participants were asked to fill a collection tube with saliva upwards to the 2 mL marker and the supplied preservative was and then added by the researcher. Samples were agitated for 10 southward to mix the saliva and preservative then stored in a common cold room (4–8 °C) until required for Dna extraction.

Deoxyribonucleic acid extraction was performed by ethanol atmospheric precipitation using reagents provided in the saliva DNA collection, preservation and isolation kit. Proteinase K was added to the sample and incubated at 55 °C for 10 min. Binding buffer B was and so added and the mix incubated for a further 5 min at 55 °C. Isopropanol was added and the sample mixed before centrifugation. Supernatant was discarded and lxx% ethanol added to the Deoxyribonucleic acid pellet. Sample was left to stand on the bench elevation for i min then centrifuged. Supernatant was then again discarded and pellet rehydrated in TE buffer. Sample was incubated at 55 °C for v min and then stored at −20 °C until required for sequencing.

ii.4. SNP Sequencing

182 Deoxyribonucleic acid samples were submitted for sequencing. Iv samples were run in duplicate equally internal controls. Sequencing of SNPs was carried out past LGC Genomics Ltd. (Middlesex, UK). I of the authors provided flanking sequencing for primer pattern taken from Ensembl. Every sample was sequenced for each of the v SNPs. Where a read could not be obtained the SNP was called as 0, otherwise SNPs were called equally per regular annotation. 68.7% of samples tests (125/182) returned a result for all five SNPs and 1.65% (three/182) of samples tested failed to return a result for whatsoever SNP. Further assay was only performed on SNPs from those individuals for whom an IAT score and an AES score could be calculated (due north = 161). The summary table (Table 1) below outlines the success rate for each individual SNP used in the assay.

2.v. Statistics

Information were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics V22.0. To assess the reliability of each calibration Cronbach's alpha was computed which represents a measure of the internal consistency of items forming a scale. The empathy measure and IAT measures were analysed using general linear models (GLMs) fitting SNPs rs2268491, rs13316193, rs4686302, rs2254298, rs53576 past presence or absence of the minor allele, gender and working in an animal care profession equally fixed effects. Residual plots were examined to confirm normality assumptions for both models were satisfied. The value for statistical significance was prepare to α = 0.05.

2.six. Participants

Participants were recruited from 4 campuses of a Higher Education Institute (Scotland's Rural College (SRUC)). Data are presented only for participants for whom an IAT score and an AES score could be calculated in add-on to at least one successful SNP assay. In total 161 people met these criteria, 56 (34.eight%) were male person and 104 (64.half-dozen%) female, 1 participants (0.vi%) did not report their gender. 97 (60.two%) of the participants reported to study in the creature intendance profession of which 80.8% (Due north = 84) were female, 46 (28.6%) reported non to report in the care profession and 18 participants did not report as to whether they study in the animal care profession. The mean historic period of the participants was 22.four years (SD = 7.97, min = xvi years, max = sixty years). Participants reported to be of British or European white ethnicity (N = 117), one participant reported to be black and the rest did non report their ethnicity. Self-reported dietary requirements evidence that 67.1% (North = 108) of the participants reported following an omnivorous diet, while 23% (North = 37) reported to following a restricted meat diet avoiding all or some creature products, the remainder 9.9% (N = 16) did not reply this question. Most, 76.iv% (N = 123) of the participants reported currently owning a pet, while 85.7% (N = 138) had done then in the past.

3. Results

iii.i. Empathy Measures

The Creature Empathy Calibration (AES) [17] showed a skilful overall reliability for the nowadays sample, Cronbach'due south α = 0.849 (N = 22). The mean empathy towards animals score was 4.3 (SD = 0.62, N = 161). Females (M = 4.91, SD = 0.54, Northward = 104) had a significantly college AES Score than males (M = 3.91, SD = 0.54, N = 56), t(158) = −7.08, p < 0.001.

In club to test the influence of the allelic combination in OXTR single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), OXTR SNPs were coded for presence or absence of the minor allele resulting in binary predictor variables [53] (Table 2).

A GLM model was used to investigate the influence of the alleles forth with gender, working in an creature intendance profession, on empathy towards animals (AES). Results bear witness that working in an animal care profession and being female are predictors of empathy towards animals (Table 3). An association with college empathy towards animals was observed for SNP rs2254298 (Table 3).

3.2. Implicit Associations to Animals (IAT)

Participants of the present report had an boilerplate IAT score of M = 0.035 (SD = 0.22, N = 161). This score did differ significantly from null (t = one.98, df = 160, p = 0.049). Females (Thou = 0.07, SD = 0.19, N = 104) had a significantly college IAT Score than males (M = −0.03, SD = 0.25, N = 56), t(158) = −2.93, p = 0.004.

A GLM model was used to investigate the influence of the alleles forth with gender, working in an beast care profession on implicit associations (IAT score). The results found that only rs53576 showed an association with the IAT score (Table four).

No correlation between implicit associations towards animals and empathy towards animals was plant (r = 0.144, N = 161, p = 0.068).

4. Discussion

The present study investigated the effect of allelic variation at v SNP loci on the OXTR (rs2268491, rs13316193, rs4686302, rs2254298, rs53576) which had previously been shown to associate with human being-homo empathy and other pro-social traits [28,29,30,31]. The present study investigated if OXTR SNPs also associate with empathy to and implicit associations with animals. The animal empathy calibration (AES; [17]) we practical showed good internal reliability; Cronbach's alpha = 0.849 exceeding reported reliabilities of 0.71 [54] and 0.78 [17]. Results of the nowadays written report plant that females had higher levels of empathy towards animals than male participants a finding previously reported in other work [17,55]. Furthermore, pet ownership and working in an brute care profession were significantly associated with higher levels of empathy towards animals. These results confirm previous results investigating farmers' [18] veterinarians' [20] empathy towards animals and their power to recognize pain in cattle. The scores for the AES also showed a significant association with one of the genotyped SNPs (rs2254298). Homozygous G individuals reported higher levels of empathy towards animals than minor A allele carriers. However as in this sample there were but 2 homozygous A individuals, due to the fact that the present sample comes from a European population where the A allele is quite uncommon (http://grch37.ensembl.org), it is impossible to say if this issue was diluted in heterozygous individuals compared to AA homozygotes. Furthermore, OXTR rs2254298 has also been shown to be involved in emotional empathy in schizophrenic and salubrious individuals [35]. In guild to also investigate implicit associations of animals the present study employed an implicit association job (IAT) to evaluate the furnishings in dependence of allelic variation. Results show that participants' (male and female combined) associations with animals were slightly positive indicating positive implicit associations with animals. Furthermore, female participants showed higher IAT scores once more indicating that women are more melancholia and empathetic towards animals [5,17]. The results of the GLM did bespeak associations between the predictor variables care profession, rs53576 and the IAT score. Interestingly, results of the nowadays report did non show a peachy variation in IAT scores, with participants' implicit associations of animals being assessed every bit only slightly positive. Further research could investigate a broader sample including non-pet owners and people with differing degrees of attachment or liking of animals and or attachment to pets to account for a greater variation in both implicit measures and explicit measures.

5. Conclusions

The study for the first time supports a role for the oxytocin receptor in enabling animal directed empathy in humans. Information technology suggests when taken in the context of the wider literature that the oxytocin receptor may provide a mutual biological substrate for both human-man and human being-animal empathy. The present study using explicit measures of empathy has also confirmed previous work showing that females express higher levels of empathy to animals. In add-on, we have shown that other characteristics (working in animal care) are associated with college human-animal empathy. Nosotros also applied for the first time a test of implicit associations to animals and found that whilst the participants in general had neutral associations, over again females had more positive associations with animals.

Author Contributions

M.C., A.B.L. and S.M.B. conceived and designed the study. M.C. provided and prepared the psychological measures; Due south.M.B. provided and conducted the biological methods. A.B.L. acquired the funding. All three authors collected the data and S.Thousand.B. conducted the DNA extraction and analysed the DNA data. M.C. analysed the empathy data and conducted the combined data analysis in SPSS. M.C. drafted the manuscript providing and discussing the psychological data and S.M.B. provided and discussed the biological information. A.B.L. proof read and edited the manuscript.

Funding

The enquiry was funded by BBSRC Strategic funding to The Roslin Institute, and from the Scottish Regime's Rural and Environment Science and Belittling Services Sectionalisation (RESAS).

Acknowledgments

We would similar to acknowledge the staff and students at the SRUCs Barony, Oatridge and Elmwood campuses and in detail Karen Martyniuk, Andy Leonard and Ann Wood their support and help in this study. We would also similar to acknowledge Helen Dark-brown (Roslin Institute) and Juan David Arbelaez Velez (IRRI) for their statistical advice.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the pattern of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hemsworth, P.H. Man–animal interactions in livestock production. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2003, 81, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, M.; Coleman, P.; Roberts, A. Empathic response to animal suffering: Societal versus family influence. Anthrozoös 2000, xiii, 48–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy, V.; Tribe, A.; Toukhsati, Southward.; Phillips, C.J.C. Public attitudes in india and australia toward elephants in zoos. Anthrozoös 2015, 28, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A.; McManus, C.; Scott, D. Personality, empathy and attitudes to animal welfare. Anthrozoös 2003, xvi, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, A.M. The motivational bases of attitudes toward animals. Soc. Anim. 1993, ane, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rae Westbury, H.; Neumann, D.L. Empathy-related responses to moving film stimuli depicting human and non-human being animal targets in negative circumstances. Biol. Psychol. 2008, 78, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul, E.S.; Serpell, J.A. Childhood pet keeping and humane attitudes in immature adulthood. Anim. Welf. 1993, 2, 321–337. [Google Scholar]

- Kellert, S.R.; Drupe, J.K.; Yale, U.; Fish, U.Due south.; Wildlife, Due south. Knowledge, Affection and Basic Attitudes toward Animals in American Guild; U.Southward. Fish and Wildlife Service: Washington, DC, Us, 1982; 162p.

- Plous, S. Psychological mechanisms in the man use of animals. J. Soc. Bug 1993, 49, 11–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A. Factors influencing man attitudes to animals and their welfare. Anim. Welf. 2004, 13, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, North. Empathy and sympathy: A brief review of the concepts and empirical literature. Anthrozoös 1988, 2, xv–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.H. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional arroyo. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrik, Westward. Social cognitive neuroscience of empathy: Concepts, circuits, and genes. Emot. Rev. 2012, four, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C.D.; Shaw, L.50. Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychol. Inq. 1991, 2, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D.; Polycarpou, M.P.; Harmon-Jones, E.; Imhoff, H.J.; Mitchener, E.C.; Bednar, L.L.; Klein, T.R.; Highberger, 50. Empathy and attitudes: Can feeling for a fellow member of a stigmatized group improve feelings toward the group? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 72, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Taylor, Due north.; Betoken, T.D. Empathy and attitudes to animals. Anthrozoös 2005, 18, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paul, E.S. Empathy with animals and with humans: Are they linked? Anthrozoös 2000, 13, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielland, C.; Skjerve, E.; Østerås, O.; Zanella, A.J. Dairy farmer attitudes and empathy toward animals are associated with animal welfare indicators. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 2998–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, D.; Sneddon, I.A.; Beattie, V.E. The relationship between the stockperson'south personality and attitudes and the productivity of dairy cows. Animal 2009, 3, 737–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norring, M.; Wikman, I.; Hokkanen, A.-H.; Kujala, Chiliad.V.; Hänninen, L. Empathic veterinarians score cattle pain college. Vet. J. 2014, 200, 186–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Dark-green Version]

- Ellingsen, G.; Zanella, A.J.; Bjerkås, E.; Indrebø, A. The relationship between empathy, perception of hurting and attitudes toward pets amid norwegian canis familiaris owners. Anthrozoös 2010, 23, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angantyr, Yard.; Eklund, J.; Hansen, East.M. A comparison of empathy for humans and empathy for animals. Anthrozoös 2011, 24, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connell, 50.A.; Hofmann, H.A. Genes, hormones, and circuits: An integrative approach to study the development of social beliefs. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2011, 32, 320–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, One thousand.R. The demand to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments every bit a central human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrichs, G.; Domes, Chiliad. Neuropeptides and social behaviour: Furnishings of oxytocin and vasopressin in humans. In Progress in Encephalon Research; Neumann, I.D., Landgraf, R., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 170, pp. 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- SNPedia. Available online: https://www.snpedia.com/alphabetize.php/Oxtr._(10.02.2016).Hom_1_* (accessed on fourteen August 2018).

- Ebstein, R.P.; Knafo, A.; Mankuta, D.; Chew, S.H.; Lai, P.South. The contributions of oxytocin and vasopressin pathway genes to human behavior. Horm. Behav. 2012, 61, 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tost, H.; Kolachana, B.; Hakimi, S.; Lemaitre, H.; Lemaitre, H.; Verchinski, B.A.; Mattay, V.S.; Weinberger, D.R.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. A common allele in the oxytocin receptor factor (OXTR) impacts prosocial temperament and human hypothalamic-limbic structure and function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.s.a. 2010, 107, 13936–13941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Greenish Version]

- Rodrigues, S.M.; Saslow, 50.R.; Garcia, North.; John, O.P.; Keltner, D. Oxytocin receptor genetic variation relates to empathy and stress reactivity in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21437–21441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kim, H.S.; Sherman, D.Thousand.; Sasaki, J.Y.; Xu, J.; Chu, T.Q.; Ryu, C.; Suh, Due east.M.; Graham, K.; Taylor, Due south.Due east. Culture, distress, and oxytocin receptor polymorphism (OXTR) interact to influence emotional support seeking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 15717–15721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Greenish Version]

- LeClair, J.; Sasaki, J.Y.; Ishii, Thousand.; Shinada, Thou.; Kim, H.S. Gene–civilization interaction: Influence of culture and oxytocin receptor factor (OXTR) polymorphism on loneliness. Cult. Brain 2016, 4, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apter-Levy, Y.; Feldman, Thousand.; Vakart, A.; Ebstein, R.P.; Feldman, R. Touch on of maternal low across the first 6 years of life on the child's mental health, social engagement, and empathy: The moderating role of oxytocin. Am. J. Psychiatry 2013, 170, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.J.; Parker, J.F.; Hallmayer, J.F.; Waugh, C.Due east.; Gotlib, I.H. Oxytocin receptor gene polymorphism (RS2254298) interacts with familial take chances for psychopathology to predict symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescent girls. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011, 1, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucht, M.J.; Barnow, S.; Sonnenfeld, C.; Rosenberger, A.; Grabe, H.J.; Schroeder, W.; Völzke, H.; Freyberger, H.J.; Herrmann, F.H.; Kroemer, H.; et al. Associations between the oxytocin receptor cistron (OXTR) and affect, loneliness and intelligence in normal subjects. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 33, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montag, C.; Brockmann, East.-M.; Lehmann, A.; Müller, D.J.; Rujescu, D.; Gallinat, J. Association betwixt oxytocin receptor factor polymorphisms and self-rated 'empathic business organization' in schizophrenia. PLoS 1 2012, vii, e51882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Wu, Due north.; Li Z Fau-Su, Y.; Su, Y. The clan betwixt oxytocin receptor cistron polymorphism (OXTR) and trait empathy. J. Bear on. Disord. 2012, 138, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kosfeld, K.; Heinrichs, G.; Zak, P.J.; Fischbacher, U.; Fehr, Eastward. Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature 2005, 435, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Domes, G.; Heinrichs, M.; Michel, A.; Berger, C.; Herpertz, South.C. Oxytocin improves "mind-reading" in humans. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 61, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guastella, A.J.; Mitchell, P.B.; Dadds, Yard.R. Oxytocin increases gaze to the middle region of human faces. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 63, 3–five. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leng, One thousand.; Ludwig, Chiliad. Intranasal oxytocin: Myths and delusions. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 79, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartz, J.A.; Zaki, J.; Bolger, N.; Ochsner, K.Due north. Social effects of oxytocin in humans: Context and person thing. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2011, 15, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Declerck, C.H.; Boone, C.; Kiyonari, T. Oxytocin and cooperation under conditions of uncertainty: The modulating part of incentives and social data. Horm. Behav. 2010, 57, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamay-Tsoory, South.G.; Fischer, Chiliad.; Dvash, J.; Harari, H.; Perach-Blossom, N.; Levkovitz, Y. Intranasal administration of oxytocin increases envy and schadenfreude (gloating). Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, 1000.E.; Trottier, A.J.; Bélteky, J.; Roth, 50.South.5.; Jensen, P. Intranasal oxytocin and a polymorphism in the oxytocin receptor cistron are associated with human being-directed social beliefs in golden retriever dogs. Horm. Behav. 2017, 95, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kis, A.; Bence, M.; Lakatos, G.; Pergel, E.; Turcsán, B.; Pluijmakers, J.; Vas, J.; Elek, Z.; Brúder, I.; Földi, L.; et al. Oxytocin receptor gene polymorphisms are associated with homo directed social beliefs in dogs (Canis familiaris). PLoS 1 2014, 9, e83993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kis, A.; Ciobica, A.; Topál, J. The effect of oxytocin on human-directed social behaviour in dogs (Canis familiaris). Horm. Behav. 2017, 94, twoscore–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Houwer, J. What are implicit measures and why are we using them. In The Handbook of Implicit Cognition and Addiction; Jon Wiers, R.West.H., Stacy, A.W., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Slovic, P. The construction of preference. Am. Psychol. 1995, fifty, 364–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vignemont, F.; Singer, T. The empathic brain: How, when and why? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2006, 10, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpinski, A.; Steinman, R.B. The single category implicit association exam equally a measure out of implicit social cognition. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 91, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwald, A.G.; McGhee, D.East.; Schwartz, J.50.K. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association exam. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1464–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparklebox. Available online: www.sparklebox.co.uk (accessed on 14 August 2018).

- Uzefovsky, F.; Shalev, I.; Israel, Due south.; Edelman, S.; Raz, Y.; Mankuta, D.; Knafo-Noam, A.; Ebstein, R.P. Oxytocin receptor and vasopressin receptor 1A genes are respectively associated with emotional and cognitive empathy. Horm. Behav. 2015, 67, lx–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I.; Forkman, B.; Paul, East.S. Factors affecting the human interpretation of dog behavior. Anthrozoös 2014, 27, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, Southward.; Herzog, H.A. Personality and attitudes toward the treatment of animals. Soc. Anim. 1997, 5, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Effigy one. Examples from the IAT representing possible evaluation tasks.

Figure 1. Examples from the IAT representing possible evaluation tasks.

Table ane. Summary of Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling success rates. Hom (Homozygous) 1 and Hom 2 refer to the alleles as they appear under the SNPs in the table. That is, for rs2268491, C is allele 1 and T is allele 2. Hom 1 individuals at rs2268491 would be homozygous for C and Hom 2 individuals homozygous for T; Het (Heterozygous) individuals would be CT. Success rate of the assay is noted in the terminal column as the % of samples submitted that returned a read.

Table i. Summary of Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) calling success rates. Hom (Homozygous) 1 and Hom 2 refer to the alleles as they appear nether the SNPs in the table. That is, for rs2268491, C is allele ane and T is allele 2. Hom 1 individuals at rs2268491 would exist homozygous for C and Hom 2 individuals homozygous for T; Het (Heterozygous) individuals would exist CT. Success rate of the analysis is noted in the concluding column as the % of samples submitted that returned a read.

| SNP | Hom ane | Het | Hom 2 | Full | % of Submitted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2268491 (C/T) | 129 | 19 | one | 149 | 92.five |

| rs13316193 (C/T) | sixteen | 49 | 55 | 120 | 74.5 |

| rs4686302 (C/T) | 121 | 29 | 1 | 151 | 93.eight |

| rs2254298 (M/A) | 104 | 25 | ii | 131 | 81.4 |

| rs53576 (G/A) | 64 | 51 | fourteen | 129 | 80.ane |

Table 2. Distribution of OXTR SNPs for the nowadays sample coded every bit presence or absence of the minor allele.

Table two. Distribution of OXTR SNPs for the present sample coded every bit presence or absence of the minor allele.

| SNP | Coding | N Male | Due north Female | Total N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2268491 | CT/TT (t present) | 6 | xiv | twenty |

| CC (t absent) | 45 | 83 | 128 | |

| rs13316193 | CT/CC (c nowadays) | 25 | xl | 65 |

| TT (c absent) | nineteen | 35 | 54 | |

| rs4686302 | CT/TT (t present) | 10 | 20 | 30 |

| CC (t absent) | 43 | 77 | 120 | |

| rs2254298 | AA/AG (a present) | vii | twenty | 27 |

| GG (a absent-minded) | 38 | 65 | 103 | |

| rs53576 | AA/AG (a present) | 23 | 41 | 64 |

| GG (a absent) | 21 | 43 | 64 |

Tabular array 3. Test of model furnishings Type I, that is, parameter estimates, dependent variable AES.

Tabular array 3. Examination of model effects Blazon I, that is, parameter estimates, dependent variable AES.

| Predictor | β | Wald χ2 (one) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intendance profession | −0.356 | iv.97 | 0.026 |

| Gender | −0.456 | 8.81 | 0.003 |

| rs2268491 | −0.687 | two.61 | 0.106 |

| rs13316193 | 0.094 | 0.74 | 0.391 |

| rs4686302 | −0.211 | 2.39 | 0.122 |

| rs2254298 | −0.799 | 4.12 | 0.042 |

| rs53576 | −0.356 | 0.001 | 0.972 |

Tabular array 4. Test of model effects, i.due east., parameter estimates, dependent variable IAT score.

Table 4. Test of model effects, i.e., parameter estimates, dependent variable IAT score.

| Predictor | β | Wald χ2 (1) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Care profession | −0.086 | ii.38 | 0.123 |

| Gender | −0.020 | 0.15 | 0.701 |

| rs2268491 | −0.126 | 0.73 | 0.392 |

| rs13316193 | 0.070 | iii.38 | 0.066 |

| rs4686302 | −0.006 | 0.02 | 0.898 |

| rs2254298 | 0.033 | 0.06 | 0.807 |

| rs53576 | 0.099 | 6.11 | 0.013 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/8/8/140/htm

Posted by: whitesuccall.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Empathy With Animals And With Humans: Are They Linked?"

Post a Comment